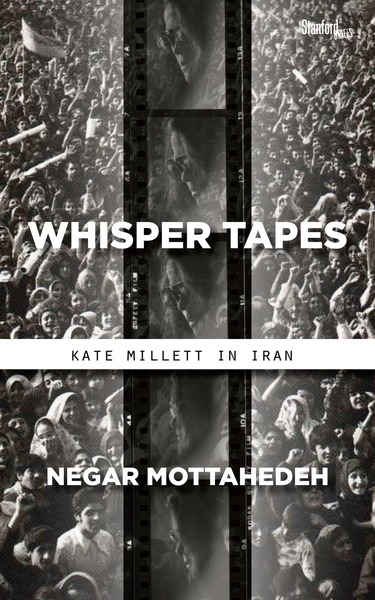

Negar Mottahedeh: Whisper Tapes

In her book “Whisper tapes” Negar Mottahedeh relistens to the cassette recordings made by American feminist icon Kate Millett during feminist protests in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution around March 8th 1979.

“The American feminist Kate Millett arrived in Tehran just after the Iranian Revolution and just before the Persian New Year. It was an exciting time of national regeneration and seasonal transformation. Spring had sprung. A new cycle had begun and, for the nation, the vision of an unpresentable future, a future never seen before, was within grasp.On March 8, 1979, less than two months after a revolution that overthrew Iran’s ruling monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah, International Women’s Day celebrations were held in Iran. This was the first time in over fifty years. While Persian queens had ruled long before the dawn of Islam and a vivid feminist consciousness had coursed through Iranian literature and poetry as early as the nineteenth century, the Shah had banned the celebration of International Women’s Day, decreeing instead that women celebrate the anniversary of his father’s authoritarian, pro-Western ban on public veiling on January 8, 1936.1 And so the choice to celebrate March 8 as International Women’s Day was in itself a symbol of a revolution that women had fought and won, hand in hand with men, against an autocratic Shah. Millett, who had opposed the Shah’s tyrannical rule from the United States, received an invitation to be one of the event’s international speakers. She was the only invited Western speaker to actually arrive.

[…]

News clippings from Tehran show Millett with a portable cassette tape recorder in hand, her “memory box,” into which she “whispered” observations on her surroundings as she captured the voices of the Iranian women with whom she joined in six days of protest. With no training in the Persian language, commonly referred to as Farsi by Persian speakers, Millett was a stranger to the instincts of the Iranian women around her (see entries x, xiv, xviii). Her audiocassettes, factory manufactured to pick up all sound, captured an auditory landscape of which she was unconscious: the sentiments of Iranian women everywhere. Millett’s “whisper tapes” thus stored the spectacular soundscape of an unfettered, imaginative, and flickering moment of verve in Iran, until the final order of Millett’s expulsion by the Iranian interim government on the morning of March 18, 1979. The following morning Millett was deported. No charges were recorded.Millett’s tapes are in many ways monuments to the articulation of a present she recognized as the beginnings of a women’s movement in Iran and, in her estimation, the first record of an independent feminist movement in the Muslim world.

[…]

The ability to stop, rewind, rerecord, and fast-forward on hand-held recording devices connects times and otherwise disjointed spaces. This happens on the tapes as I listen. Millett does this consciously sometimes, and at other times it seems reflexive, absentminded. The unwinding and fast-forwarding of the tapes unmoor the predictability of the things I take as tangibles, things we all take for granted: this moment, that time, this person, that space. Spaces and people appear and disappear, sometimes randomly because of the technology itself.”