Elske Rosenfeld, A Bit of a Complex Situation, 2-channel video, 2014

Material: Excerpt of a video recording of the first session of the Central Round Table of the GDR, 7 December 1989, East Berlin (courtesy of the Robert Havemann Gesellschaft e.V./ Archive of the GDR Opposition). At its first meeting, members of the new political groups and citizens movements and of the established parties came together to discuss the role of the Round Table in aiding the democratic transformation of the country. The session was recorded unofficially by Klaus Freymuth (1948-1991), an independent filmmaker and member of the oppositional New Forum.

Material: Excerpt of a video recording of the first session of the Central Round Table of the GDR, 7 December 1989, East Berlin (courtesy of the Robert Havemann Gesellschaft e.V./ Archive of the GDR Opposition). At its first meeting, members of the new political groups and citizens movements and of the established parties came together to discuss the role of the Round Table in aiding the democratic transformation of the country. The session was recorded unofficially by Klaus Freymuth (1948-1991), an independent filmmaker and member of the oppositional New Forum.

To interrupt is to stop something, to cause a break in the continuity of a process or a condition, in its uniformity, to break this something off in the middle. One can interrupt a person to get them to stop what they are doing, or one can interrupt someone who speaks. In computers one speaks of an interruption, if one programme is stopped, so that another procedure can be carried out. In its Latin origin (rumpere), it is connected to notions of breaking, uprooting, bursting, tearing, rupturing, breaking asunder, or forcing open.

The moderator stands, his hands folded in front of his torso. He lifts his hands. His right hand flies up to his chin, the other comes to rest in the nook of his right armpit, holding up his left arm across his chest. His head is turned slightly to the right, towards where another man reads from a text. His head turns left, towards the door, towards the sound of someone entering the room.

The chin lifts slightly, as if to signal a question. His right hand gestures a quick, more emphatic question to the person that has just entered the room. Then he taps his right ear twice, rapidly. His hands sink down, his head lowers too, then lifts up again with a questioning expression while his hands surrepititiously (nervously?) pick up a pen from the table.

The right hand follows the right pointed finger up towards the speaker on the right. The head turns right, too. The finger tries to catch the speaker’s attention, bopping up and down twice, then it sinks down – it has not been seen. Both hands sink down, momentarily defeated.

The head tilts forward and right, toward the man seated there, a short nod. The right hand and pointed finger fly up again, higher this time, catching the attention, now that the man has concluded his speech.

“If I may briefly interrupt,” says the moderator and passes the word to the person who has entered the room outside the frame.

A short scene, recorded on video during the first meeting of the Central Round Table of the GDR︎︎︎ in December 1989, where a noisy demonstration gathers outside the assembly hall. It is December 7th, 1989, and the Central Round Table of the GDR has come together for the first time; a meeting has been called by oppositional groups and mediators from the Catholic and Protestant Church, to negotiate between the demands of the revolutionary groupings and the established political organisations, whose legitimacy has come into doubt over the past two months. From the unstructured openness of the mass-demonstrations, protagonists have been asked inside, into the emerging forum of the Round Table, to give voice and concrete shape to the revolutionary demands. On this, the first day, the plan is to negotiate the rules of procedure, the prerequisites for admitting participants, the Table’s function and role for the coming months. But now, only a few hours in, procedure is suspended, as a sound of shouting and whistling makes itself heard outside of the windows of the room.

an inter//

ruption

inter//

rup

ts

The camera pans frantically to the right, and stops on the man, who stands by the door. He starts so speak and points at the window every now and again: “There is a big mass of people outside. They have drums and whistles and they are shouting… It is a pretty big group. I hope they are not going to come inside. At the moment they are just outside the doors. But expectations are running high. That’s what I wanted to say. The noises you are hearing are coming from the outside.”

The camera pans back to the left of the room, a participant begins to speak, a discussion commences, participants try to agree on a response.

The groupings lining the left side of the table are the “new forces”: members of new political groupings that have been active in different circles of the oppositional underground – the peace, civil rights and environmental movements, critical Marxists, women’s groups, Social Democrats, one or two liberals. The contrast between the oppositionals, most of them in woolly sweaters, with unruly hair, rocking on chairs, fumbling nervously, and the professional politicians, who sit on the right side of the table, is sharp. From the side of the state-socialist groupings, only the younger, more reform-oriented members are active in the conversation, the rest sit, in brown and black suits, motionless. Those of the more active and involved younger reform socialists, who speak, are trained and fluent in the language of speaking publicly. The revolutionaries are struggling notably to express themselves in a language that could be deemed fitting for the situation in which they find themselves for the first time.

Ingrid Köppe, a member of the New Forum says:

“Yes, but a delegation that makes a joint declaration then, not just one representative from the SDP, who tries to negotiate, …”

“Yes, but a delegation that makes a joint declaration then, not just one representative from the SDP, who tries to negotiate, …”

Her left hand is on the table and holds a piece of paper in front of her, her right hand is in front of her chin pointing out into the room, while here fingers hold a pen. Her right hand moves the pen down a little and forward in the direction of the other hand and the piece of paper on the table, it moves the pen up and down quickly a few times. The left hand holding the paper comes up towards the right hand, which continues hovering in front of the chest.

Does the hand lift

or

is the hand lifted?

For ten minutes, as the sound outside swells, hasty proposals are made and then rejected – those are words that contradict each other, that seem to go around in circles, language reaches its limit. Meanwhile eyes blink nervously, bodies rock on chairs, pens are fondled and turned in hands, the camera pans frantically back and forth, feet shuffle and faces twitch. Words falter, but meanwhile, a second story tells itself between the invisible, but audible bodies approaching outside and the visible and audible jittery bodies of those assembled inside.

What does her

hand know?

Lygia Clark “Hand Dialogue”, 1966

//hands

The Brasilian artist and psychoanalyst Lygia Clark [1] writes: “My hands are a million years old […] in them, the wisdom of thousands of years, hands that dug, planted, carried stones;” “Hands which were never finished in their definite form, hands of a skipping child, playing hop-scotch […] Hands which now dig my grave;” “Feeling the world by its form, knowledge which goes far beyond the eyes.”

In The Gesture of Making[2], Vilèm Flusser, the Czech-born philosopher and communication theorist, writes about hands, and the way they grasp the world in the act of touching and making things. He writes about how the act of clasping an object, and shaping it, is that which combines the two hands of a person into a whole. The body mediates its inherent incompleteness, its dependence on an Other through this motion of the hands.

“grasping”

“seizing”

“apprehending”

“comprehending”

“seizing”

“apprehending”

“comprehending”

Harun Farocki “The expression of the Hands” , 1997

In “The expression of the Hands,” Harun Farocki flicks through a book that instructs actors in the psychology, the signology of the hand. He says: To show the inside of the hand is to show the emotions of the soul, to show the outside, the emotions of the thinking mind.

Still from Harun Farocki “The expression of the Hands”, 1997

Still from Harun Farocki “The expression of the Hands”, 1997“Blue Gloves” An exercise as part of the workshop “Corporeal Dis/continities – what bodies know of state socialism”, developed 2019 by Suza Husse and Elske Rosenfeld for The Whole Life Academy, organised by Haus der Kulturen der Welt, with: Charlotte Eifler, Nour Hachem, Rita Hajj, Susanne Hopmann, Ashoka Vardhan.

Anike Joyce Sadiq, “Visited by a Tiger”, 2019 ︎︎︎

A video piece in two chapters. A conversation between the fist as a model of the brain and as the iconic symbole for struggle, resistance and solidarity

HD video, 9:16, 11 min, stereo sound

Installation shot

Köppe’s hand circles in front of her. She taps the paper with the pen. She lowers her hands towards the table, she presses against it with the backs of her hands, pushing herself back for emphasis, after she has made her point. She sits still for a few seconds, before the camera pans away.

During the ten-minute scene, the sounds from the outside ebb and flow while the debate inside, at the table, intensifies. The question is: Who are the people outside and what might they want? Are they here in support and if so, of who? Are they a threat? The participants’ words try to seperate an inside from an outside.

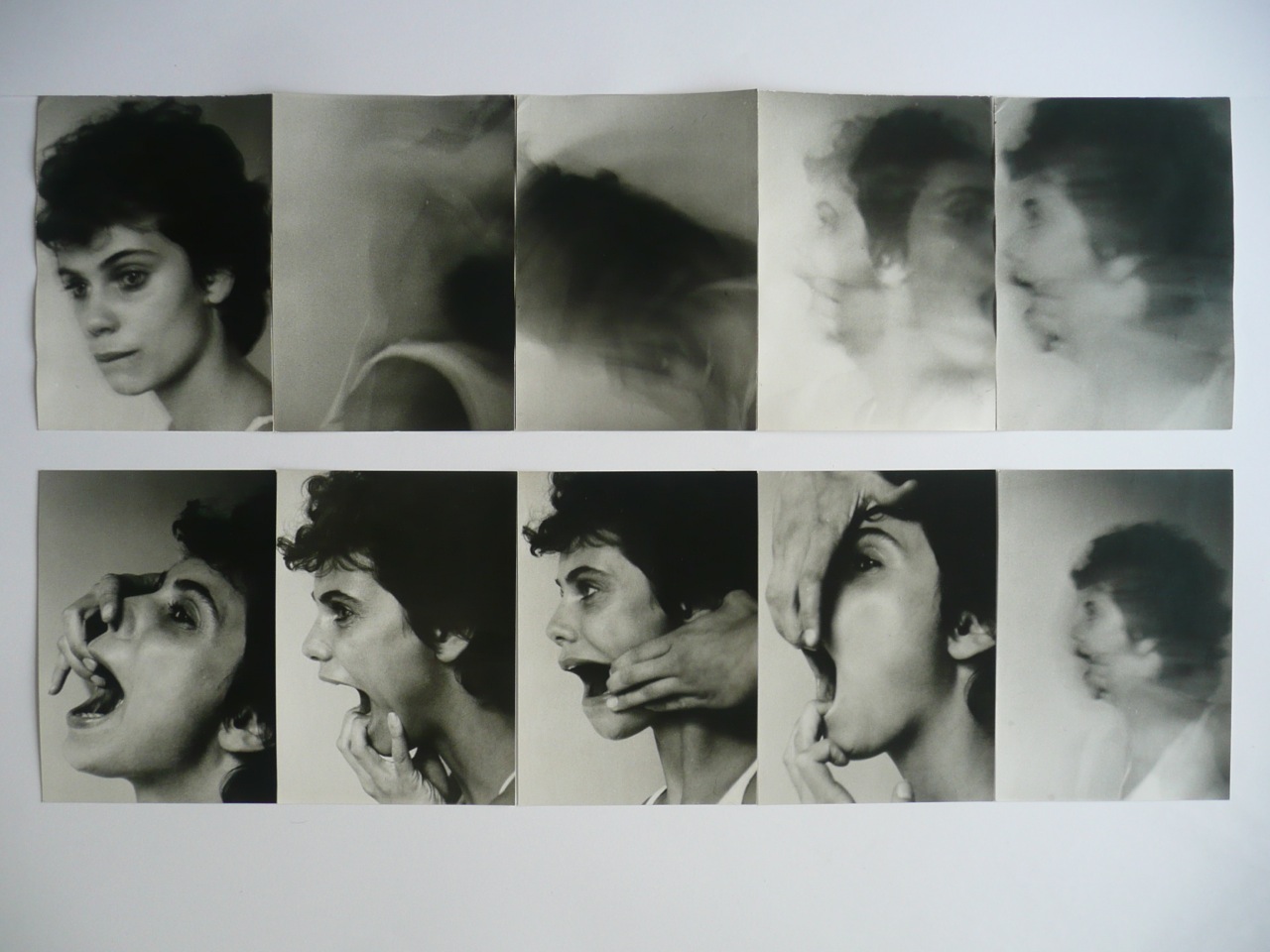

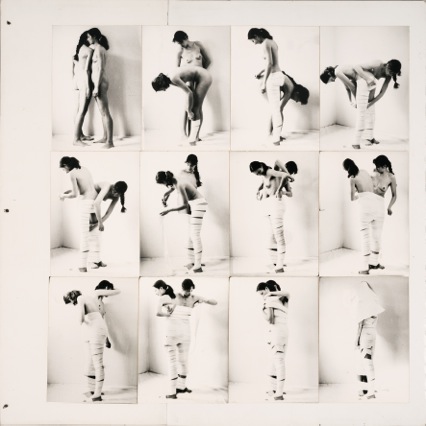

Gabriele Stötzer, “Gesten” [Gestures], 1981)

Gabriele Stötzer, “Gesten” [Gestures], 1981)Photo: Cornelia Schleime

What does

language

hide?

“It’s the 7th today,” says Ulrike Poppe, “And there have been calls, as some of you know, for a clear statement about the electoral fraud.”

Her right hand, loosely curled into a fist, hovers next to her temple, blocking parts of her face and her mouth from sight. Fingers release, a second later, towards a man who is trying to interrupt her from the Table’s right-hand side. Her hand keeps the space open, in which she can complete her sentence, while she raises her voice.

Stötzer writes: “in the gestures, that i made when i was alone (and that cornelia schleime photographed), i tried to communicate something with my hands that i sensed within myself (in my function as a medium), but that i did not yet know and could not yet communicate.”

“signals was about something obscured, it called on something other, not yet speakable.” [4]

“Sign//

als”

Gabriele Stötzer, an East German performance artist made a number of works, photographic series and films (often as part of the Künstlerinnengruppe Erfurt[3], which she co-founced) that use hands and bodies as media of the collective signallings of her and her collaborators.

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Gesten” [Gestures], 1981

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Gesten” [Gestures], 1981

At the Round Table, the walls separate the rowdy mass outside from the relative order within. But the fear of the participants that the masses may spill into the room is palpable. The walls’ stability appears to be in doubt as the wall is perforated by the swelling sound of voices, whistles, and drums.

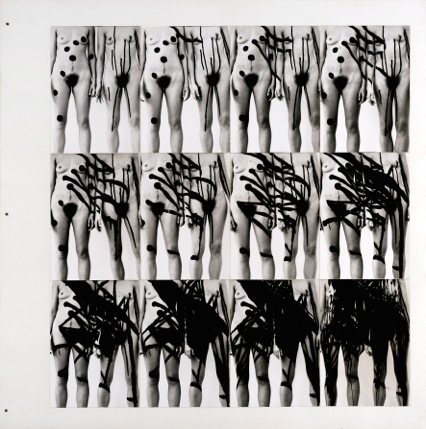

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Mumie” [Mummy], 1983

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Mumie” [Mummy], 1983The participants inside are separated, one from the other, each into a body, an individual, as they say, by their skin.

The walls separate the assembly hall from its outside.

The walls separate the assembly hall from its outside.

s//

kin

kin

A dance piece by Jérôme Bel (”jérôme bel”, 1995) investigates the skin in its constructedness, its inscription as the limits of the individual, the marker of the subject’s boundedness. Throughout the piece, the skin of the dancers is stretched, marked, literally branded and written upon, and revealed as semantic, as overwritten with text. Such are the inscriptions that stabilise the skin as a seemingly impenetrable boundary of the self; it is only through such an inscription of the skin, that the seamless overlap, the complete coincidence of the body and the subject can be assured.

Documentation Jérôme Bel, “jérôme bel”, 1995

Documentation Jérôme Bel, “jérôme bel”, 1995

Gabriele Stötzer, “Schrei Carmen” [Scream Carmen], 1983

In Gabriele Stötzer’s “Mummy” (1983) the bandage becomes the skin. In “Einwicklung” [Wrapping] (1982) two women are shown wrapping themselves in bandages until they become one body with two heads and varying numbers of limbs. In the written and drawn upon photographs of another series (“Verschmelzung“ [Fusion], 1982), slithers of paint drip or stretch from one body to another, morphing bodies into one. In “Schrei Carmen“ [Scream Carmen] (1983) a woman’s mouth is pulled wide open by a hand or a set of hands. In all of Stötzer’s photographic and filmic experimentations, bodies, alone or in collective constellations, are wounded, fragile, vulnerable to and interpenetrating with the world.

Gabriele Stötzer, “Einwicklung” [Wrapping], 1982

Gabriele Stötzer, “Einwicklung” [Wrapping], 1982A body that makes nothing of the “closed, smooth, and impenetrable surface” of the skin.[5]

M.M. Bakhtin

How close is

your skin?

Gabriele Stötzer, “Verschmelzung” [Fusion], 1982

Gabriele Stötzer, “Verschmelzung” [Fusion], 1982“We are in a bit of a complex situation,” says the moderator whom the camera finds after a small pan to the right. “We just had an intervention regarding something very fundamental, and are suddenly confronted with the necessity to act, if I understand well.”

Unlike the other participants, the moderator speaks standing up.

His hand, which was nestled into the other hand below his torso some seconds ago, points forward now, into the room, as he says, “I have one request to the documentarists. Please don’t ask anyone to go outside.”

Behind the speaker, another participant’s body moves in and out of sight. Behind, and slightly above the speaker from this angle, Ulrike Poppe turns her face a little more into view, towards her right. She leans her torso back a little to adjust her chair, she lifts her head above Wolfgang Ullmann’s head while doing so. Her torso swings forward again, her chair is pushed back by hands that are hidden by Ullmann’s body to her right. Her torso slides backwards, it emerges again, behind, or, to the left of her neighbour, as she sits down. Her torso, her head, her face in profile, is fully in view now that she has moved back and out of the other bodies’ staggered line. Off-screen, but close to the camera, another man repeats the first man‘s message:

“There is a big demonstration outside.”

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Das Loch” [The Hole], 1982

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Das Loch” [The Hole], 1982What is the language

of the

eye?

the grote

sque///

bod

/y

She lifts her head above that of the man to her right. “Now we are hearing it”, she says before lowering her head again, turning it left and out of sight.

She is leaning forward, she is listening intently. Her shoulders, taut with attention, catch the glare of the overhead light. She swings her torso backwards and her face and eyes swivel around as if trying to find the eyes of the woman to her right.

“The grotesque […] is looking for that which protrudes from the body, all that seeks to go out beyond the body's confines. Special attention is given to the shoots and branches, to all that prolongs the body and links it to other bodies or to the world outside.”[6] “The object transgresses its own confines, ceases to be itself. The limits between the body and the world are erased, leading to the fusion of the one with the other.”[7]

M.M. Bakhtin, the early Soviet literary scholar and philosopher,

describes the “grotesque body” as a body that is “terrorized by the state, and in being terrorised transforms itself into a body that is forever incomplete, connected to the world; that joins with others to transgress its own limits and “make the world whole”.[8] Bakhtin was forcefully exiled to Kazakhstan during the Stalinist purges, and lost a leg during this time.

A voice, off-camera:

“I want to go and stand outside before things escalate further. Without making an authorised statement. And I would ask two or three of you, if you all agree, to join me in going outside.”

The camera pans to the room’s right time again, but more slowly this time.

“I want to go and stand outside before things escalate further. Without making an authorised statement. And I would ask two or three of you, if you all agree, to join me in going outside.”

The camera pans to the room’s right time again, but more slowly this time.

the h o le

Stötzer writes: “i photographed all holes on them as entrances, painting black stripes as exits, connecting two women through exiting and entering lines, piled the naked bodies of women into a towering stack that i photographed from the front and from behind, i presented the connection between a woman and her surroundings by having her press her body against a pane of glass in order to be able to record the reaction of her flesh, i wrapped a whole body in bandages as a wound, until it turned into the final, classical shape of an egyptian mummy that brought a promise of aesthetic healing along with it.”[9]

& the

////// protru

berance

////// protru

berance

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Das Loch” [The Hole], 1982

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Das Loch” [The Hole], 1982In 1979 Gabriele Stötzer was sentenced to prison for defamation. During her incarceration she was misdiagnosed with an ectopic pregancy and operated on, leaving a permanent scar. “It is my symbol of my time in jail, my barbed wire. It is what I took with me to the outside.”[10]

How whole

is a

hole?

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Verschmelzung” [Fusion], 1982

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Verschmelzung” [Fusion], 1982How hole

is a

whole?

“In the post-totalitarian system, this line runs de facto through each person, for everyone in his or her own way is both a victim and a supporter of the system.”

In his 1978 essay "The power of the powerless", Czech dissident and playwrite Havel describes the line of conflict between the system and opposition to it as one that runs through the body itself.

The body of the post-totalitarian subject is a place where the system intermingles with its outside.

On the left side of the Round Table, a man is returning to his seat. He sets the whole row of bodies in motion while he sits down. Faces, heads, checks, mouths and noses, backs and necks swing back and forward. It takes some seconds for the commotion of bodies to quieten back down.

The camera cannot always trace the voice of a speaker back to the body.

When someone new speaks, it follows the sound. Sometimes the camera catches a speaking mouth.

The camera cannot always trace the voice of a speaker back to the body.

When someone new speaks, it follows the sound. Sometimes the camera catches a speaking mouth.

“We are faced with the question,” begins Gregor Gysi, who the camera soon finds on the room’s right-hand side. “We are really faced with the question,” he says, repeating himself, “that we should avoid any further escalation on both sides.” The sound of the demonstrators’ whistling and shouting is even more clearly audible through the windows now.

the

m//ou

th

A participant of the Workshop “Corporeal Dis/continities” (2019) licks a copy of a document from the German Hygiene Museum in Dresden. The original poster warns about the different modes of transmission of infectious diseases.

︎︎︎

the co

ugh

//

Stills from Video: "Brazilian president Bolsonaro filmed coughing throughout speech"

Stills from Video: "Brazilian president Bolsonaro filmed coughing throughout speech"Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro coughs during a speech surrounded by supporters protesting the ongoing Brazilian lockdown due to the global coronavirus epidemic. ︎︎︎

„Did you go outside?,” asks the moderator, “Did you make a statement?” “Do you think it is necessary?”

„I believe things are heating up, yes,” the man replies.

„I believe things are heating up, yes,” the man replies.

What can

the body

contaminate?

Still from Wolfgang H Scholz: Historical Overlay 2021-10, performative research with Elske Rosenfeld, in a setting by Suse Weber (Camera: Aida Kadrispahic); with excerpts from Wolfgang H. Scholz, “Zustand 1988”, movement and temporal study,, Dresden 1988, with Heike Hampel and Fine Kwiatkowski (pictured here), Wolfgang H. Scholz, “Body Building”, 1988; and a sound recording of a speech by the Head of the GDR’s Stasi (secret police), Erich Mielke, held during a meeting with leading functionaries, 1982.︎︎︎

Does the torso

have a sound?

Sound recording of a speech by the Head of the GDR’s Stasi (secret police), Erich Mielke, held during a meeting with leading functionaries, 1982

mielke

///cou

ghs

///cou

ghs

Wolfgang Ullmann has been holding up his hand to ask permission to speak for quite some time - until he is, finally, being granted the word. “I am really the last person who wants to escalate anything, so I won’t insist on that word,” he says. His finger is pointing forward, towards the previous speaker now. Behind him the camera catches the smear of the woman’s face, her hair, her wooly jumper, smudged by her movement as she sits back down.

double

st//um

bl/

e

st//um

bl/

e

Piotr Bikonts film „Double Stumble,“ (1989) shows a scene in which Polish leader Wojciech Jaruzelski walks into a room where a meeting of high-ranking representatives of the Polish government and the Solidarność movement is about to take place. Media researcher Philipp Goll writes: “What we see is a preliminary editing process on the screen, in which a sequence for a broadcast is to be created. An editor edits scenes from a political summit [...] into a ‘smooth’ sequence. Bikont records the creation process. Scenes are edited in which the characters make transitions: they get out of cars, enter rooms - and scenes are cut out, such as the eponymous ‘double stumble’ of the still incumbent Polish head of state Wojciech Jaruzelski as he crosses a threshold.”[11]

Piotr Bikont, Double Stumble, 1989: General Wojciech Jaruzelski

stumblesas he steps into the meeting room.

** Piotr Bikont also made another film “The Round Table” in 1989, documenting the Polish Round Table

“Errrm”, “er”, “ahem,” Ullmann says, letting his his sentence end in a sputter. “I’m sorry he says,” tilting his head to the side appologetically. “Ja, ja,” he says, he looks down, smiling at where his hand taps the table. “I am,” he lifts his head and shoots a quick glance towards the previous speaker, “a little nervous, too.”

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Verschmelzung” [Fusion], 1982

The shouts and whistles are now almost as loud as the speakers’ voices. They mix with the sounds of the moving bodies inside, the shuffling of the chairs, the rustle of paper, the sound of glasses or bottles being set down. On the level of sound there is no way of telling inside from outside.

voice

///vs//

soun

//////d

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer,

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Schrei Carmen” [Scream Carmen], 1983

In her voiceover in Manon de Boer’s Resonating Surfaces, the Brazilian author and psychoanalyist Suely Rolnik talks about language and the body, speaking as sound, and speaking as discourse, and an insight that takes shape over a long period of time, between her youth in Brazil and her later return to there, and through her relationships with Deleuze and Guattari during her exile in France.

From the desciption of the film:

„Screams of death open ‘Resonating Surfaces’ on a whitened and scratched film. It is upon that bearer of images where no image is to be found that the two female voices – opera parts of Alban Berg’s Lulu and Wojzzeck – act out a bodily vibration, a pure vibration which manifests life and which is succeeded by silence and a dark screen. The darkness slowly gives way to takes of São Paulo, searchingly gliding over the surface of the elusive city and skirting around the rhythmic bodies and portraits of some individuals. All the while there is a song-like voice, voices loosely uttering words and memories, making the sound have its own mental room which never derives from the one that is occupied by the image. A voice of an individual starts telling a story and becomes language as well as text while, in a punctuated off-beat rhythm, the image moves to the portrait of that individual. As Suely Rolnik’s personal story grows, the voice comes to the foreground and the image vanishes into dark takes of her and bright takes of Paris, into under and overexposure so as to give room to that voice, its physical presence and the images it summons.“[12]

a song-like voice

the mental room of the voice

memories, loosely uttered

“They heard me scream and the whole floor began to scream. Because they had no idea what was happening. Someone might have been hitting me. They threw their stools against their doors. It was a spontaneous collective cry. And this was the first time I really felt these women. With this cry. Because I knew that this cry was for me.”

In an interview [13] , Gabriele Stötzer describes an incident during the first weeks of her time in prison, where she began to suffer from abdominal pains. At some point the pain got so unbearable that she started to scream. As she screamed, the women in the surrounding cells began to scream, too, to scream for her.

Detail from Gabriele Stötzer, “Schrei Carmen” [Scream Carmen], 1983

During the interruption of the Round Table the voices from the outside do not demand to be let in. As the demonstrators outside whistle and scream, the distinction between outside and inside is, however, already undermined on the level of sound – without the outside ever entering. Without ever really becoming intelligible (although the Table makes various attempts at listening and interpreting), the sounds form the outside make the speaking on the inside itself into a kind of gobbledygook. The ways of speaking that the Table is just beginning to figure out for itself become meaningless, disoriented, and dysfunctional in their encounter with the sounds of the bodies outside. And, as the language inside runs into a dead end, bodies are animated and joined together: the shouting, clapping, whistling, the rustling, the shuffling, the talking, the whispering of the bodies inside and outside become indistinguishable – one unified body of motion and sound.

Participants of a workshop in Leipzig in 2018 read out instructions to each other as they are trying to re-enact, frame by frame, movement by movement, an excerpt from the video material of the scene at the Round Table..

“13 Frames.” Collective experimentation. Workshop during „Unterbrechungen: Skripte, Proben, Gesten“ (Elske Rosenfeld and Achim Lengerer) at Kunstverein Leipzig, 2018︎︎︎

Is there a home

outside language?

Where can a silence

be nested?

a colle//

ctive in

sou///

nd

Between the Round Table and its outside, the interruption creates an impure collective in sound.

an impu

re///col

lecti

ve

After the discussion has gone round and and round in circles, a man comes in from outside and interrupts the discussion again.

He says: “If I may...

It seems that the situation is calming down a bit now. Those who were standing in front of the building have started to move again. This is to say that the demonstration is now moving past the building. No one is standing anymore. It seems as if the situation is less tense now. So, I believe, this is my personal opinion... that it is no longer necessary for someone to go outside. Because then people would stop walking once more.” He lowers his hands and takes some steps backward. The camera pans back to the left of the room, to Herr Ullmann.”

He says: “If I may...

It seems that the situation is calming down a bit now. Those who were standing in front of the building have started to move again. This is to say that the demonstration is now moving past the building. No one is standing anymore. It seems as if the situation is less tense now. So, I believe, this is my personal opinion... that it is no longer necessary for someone to go outside. Because then people would stop walking once more.” He lowers his hands and takes some steps backward. The camera pans back to the left of the room, to Herr Ullmann.”

What is the flesh of the interruption?

The demonstration outside moves on before the participants inside have reached a decision.

The day’s agenda is resumed.

The day’s agenda is resumed.