Becoming In/Visible, research, collage and script for a possible performance, Elske Rosenfeld & Olia Sosnovskaya, from 2023

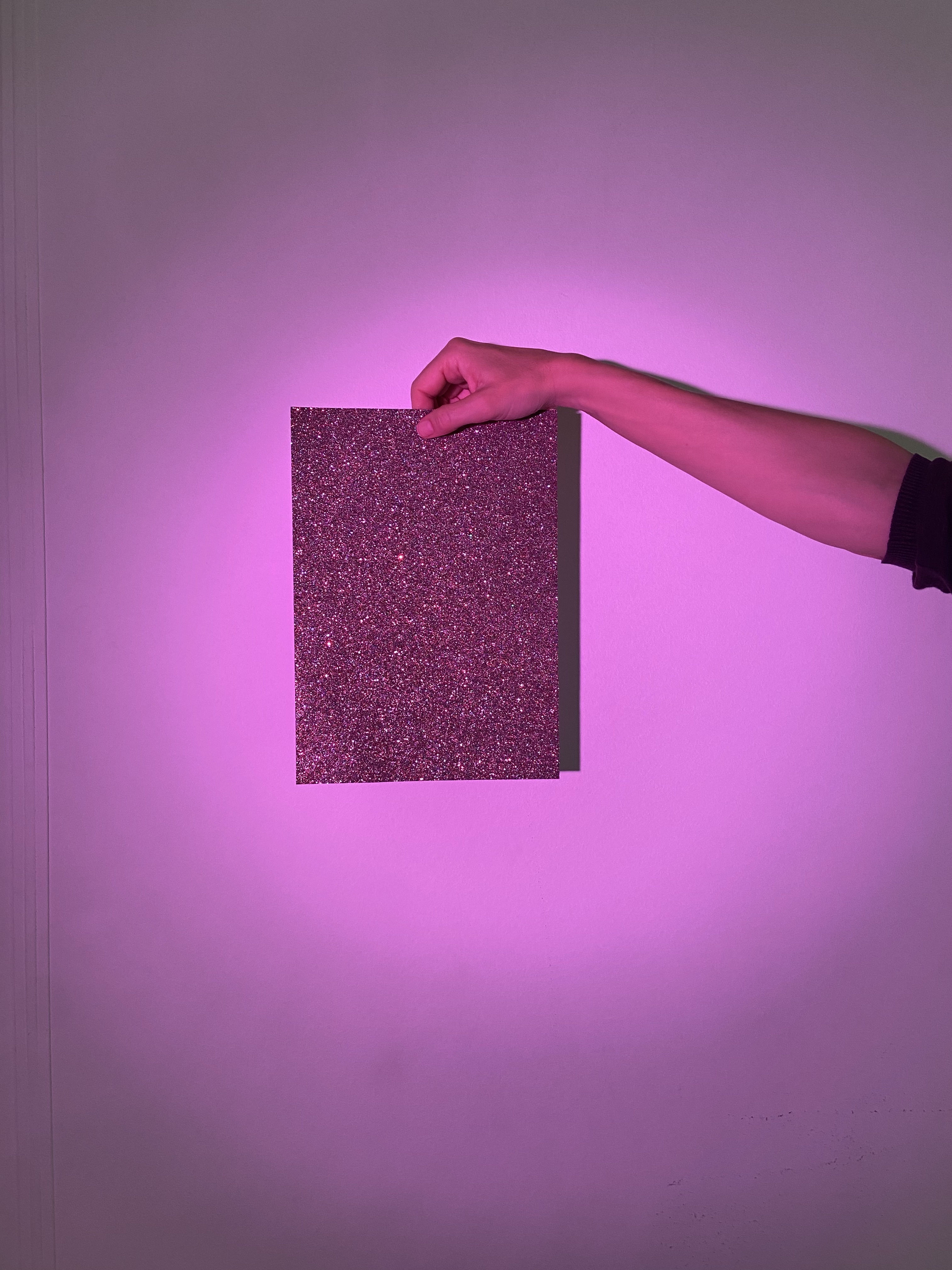

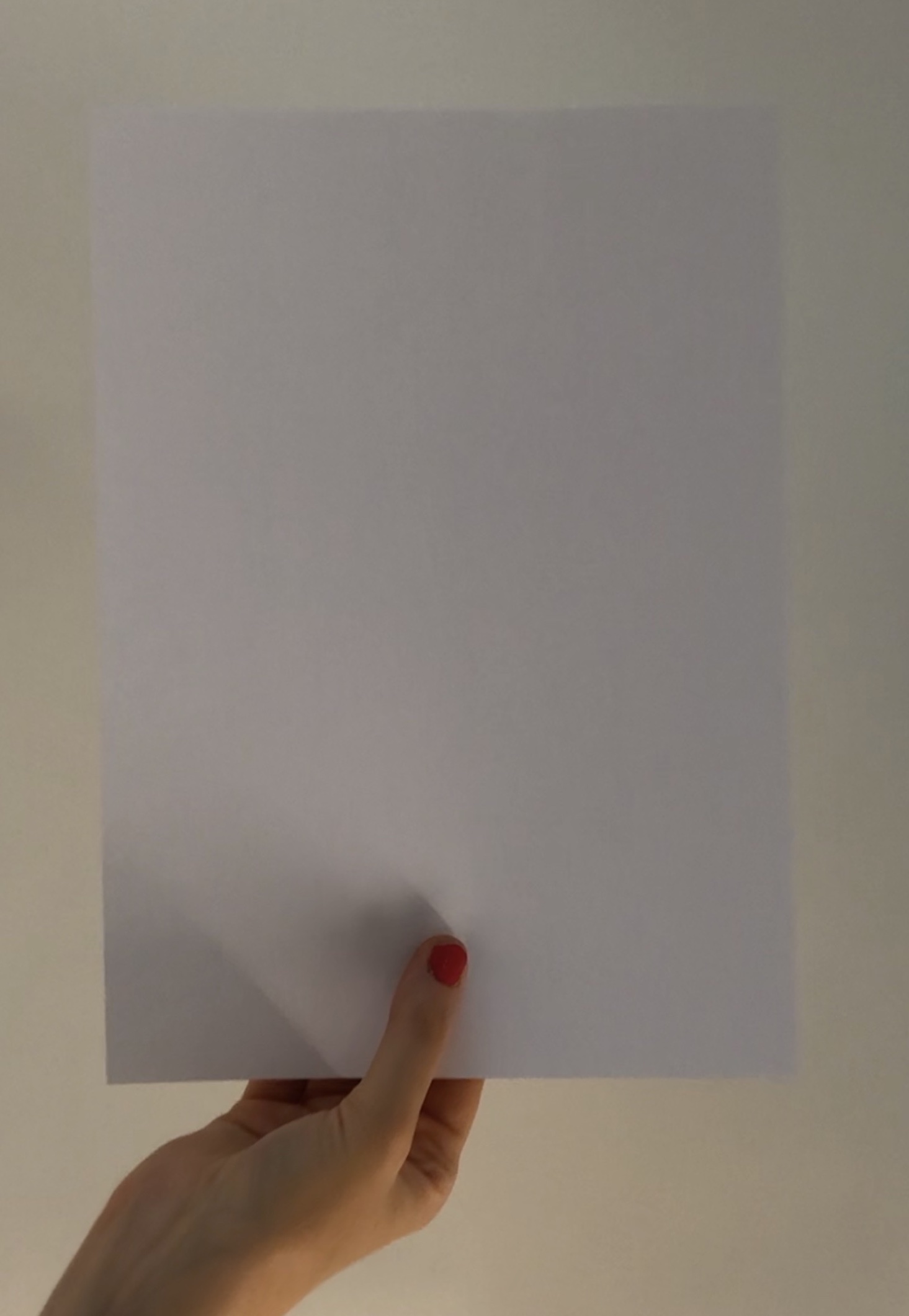

Materials: white paper, red glitter paper, pink glitter paper, coloured light filters, lights, coloured markers, a fog machine (or our desire for it), the works of Julius Koller and Jiri Kovanda, CSSR after 1968, a performance by Nadya Sayapina, Minsk 2020, an art project by Lesia Pcholka, Minsk 2020, A4 paper with the images of a confiscated art collection, A4 papers with images of police violence, a white piece of paper held up in protest in Jena 1970, in Belarus 2020, in Kazakhstan 2019, in Beijing 2020, in Russia 2020, a white piece of paper pinned to a window, a worker on strike holding A4 paper with a written statement and her ID, flags hiding the bodies of protestors. Elske’s experience of the 1989/90 revolution, Olia’s experience of the 2020/21 revolution, Asef Bayat’s concept of the non-movement in the revolution in Egypt, Ewa Majewska’s concept of weak resistance in political mobilisation in Poland, Vaclav Havel’s concept of parallel structures in Czechoslovakia, Olga Shparaga’s book “Revolution with a Female Face” on the revolution in Belarus, Johanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory,” gestures of holding (paper, lights, camera), everything, nothing.

Going, being, emerging from: underground, under the surface, the shadows. The power of invisible undercurrents, the weak power of collective actions of non-collective actors, the non—movements, networks grounded in kinship, friendship, worship, the hidden sphere, parallel structures. Invisibility as protection. Invisibility as violence. The invisibility of some forms of violence. The invisibility of something that cannot be captured by the instruments of perception and the invisibility of something that is made invisible by the instruments of perception. The invisibility of something that blends into the background. The invisibility of something that hides behind the contours of an identical object. The invisibility of the resistance inside the resistance; of a narrative inside the narrative. The invisibility of something dark hiding in the shadow. The invisibility of a light pointed at a bright sky. The invisibility of something that is always there. The invisibility of something that is not at all moving. Everything. Nothing.

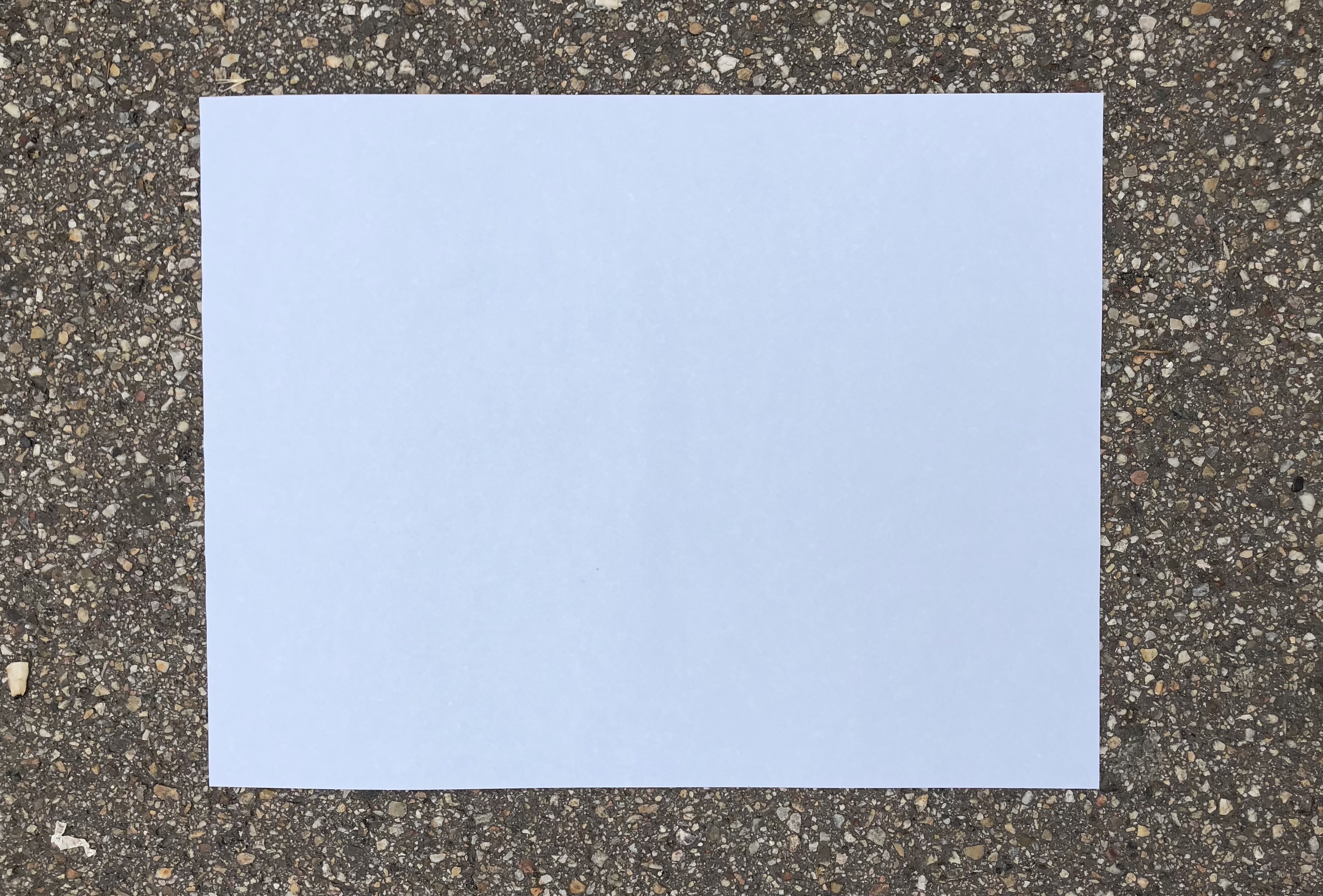

... a layer of sand covering the light grey pavement, a sheet of white paper taped to a white wall, a plume of white smoke in a lit up sky, the blurred petals of a bunch of white flowers, a white sheet of paper taped to a window in front of a pale sky, a pile of snow on white ground...

Aslan's stance initially confused the police.

The Kazakhstan police took the young activist into custody after he decided to test whether he could get away with standing in the street holding a placard with no writing on it.

Aslan Sagutdinov took the placard to the central Abay Square of his native city of Oral in the west of the country, and held it up opposite the central council offices.

The video blogger took the precaution of having a colleague capture the whole thing on video, which the local Uralskaya Nedelya news site embedded in its report.

"I'm not taking part in a protest, and I want to show that they'll still take me down the police station, even though there's nothing written on my placard and I'm not shouting any slogans," the 24-year-old told reporters who'd turned up to see what happened.

The Kazakhstan police took the young activist into custody after he decided to test whether he could get away with standing in the street holding a placard with no writing on it.

Aslan Sagutdinov took the placard to the central Abay Square of his native city of Oral in the west of the country, and held it up opposite the central council offices.

The video blogger took the precaution of having a colleague capture the whole thing on video, which the local Uralskaya Nedelya news site embedded in its report.

"I'm not taking part in a protest, and I want to show that they'll still take me down the police station, even though there's nothing written on my placard and I'm not shouting any slogans," the 24-year-old told reporters who'd turned up to see what happened.

E: After 1989/90, the revolution in the GDR essentially disappeared from official language. Chronologically, the revolution disappeared, too. The experience of a historical moment of popular emancipation disappears within the dominant narrative and chronology of the successful “Fall of the Wall” and the “Happy Reunification.” In this version of history there was no revolution.

When I talk to protagonists, there is a disjuncture between the excitement that passes between our bodies and the way it is immediately disavowed in words. We tell ourselves that it was nothing of importance, that “we were naive” to believe in what we believed in, but our bodies tell a different story.

When I talk to protagonists, there is a disjuncture between the excitement that passes between our bodies and the way it is immediately disavowed in words. We tell ourselves that it was nothing of importance, that “we were naive” to believe in what we believed in, but our bodies tell a different story.

In the summer of 2020, the painting “Eva” (1928) by Chaïm Soutine, among other artworks, was confiscated by the Belarusian state from the art collection of Belgazprombank, whose head, Victar Babaryka, decided to run for president. That time the protests were already starting in the streets of Minsk. They later erupted into the massive anti-government uprising, of which women were often the driving force and the face. Belarusian philosopher and activist Olga Shparaga tells this story in her book “Revolution with a Female Face”. “The end of invisibility” is the name of the first chapter of her book.

O: It took me a while to become hopeful about this protest, because there had already been so many failed ones. And as soon as I believe in it, it also feels like I can't let it go. Maybe if I do, I will never be hopeful again. I still do think that the revolution in Belarus is not over, at least in the sense that there won't be any normality or any return to the status quo in society after what happened.

Aleksei Borisionok writes: “Eventually, the main painting of the collection, Éva, representing the portrait of an unknown Jewish woman, became the symbol of protests, gaining popularity in the country. Cultural workers, professional and amateur artists started to produce imagery connected to the painting: t-shirts, stickers, posters, memes. Some of the protest campaigns feature her as a symbol and the face of Belarusian protest. The image has become one of the precursors of the strong position of women in the protest activities against police and state violence.”

Olga Shparaga talks of the beginning of the revolution in Belarus as the moment of something becoming invisible and something

becoming visible

at the same

time.

of the revolution as the moment of something

becoming invisible and something

becoming visible at the same

time.

something becoming invisible and something

becoming visible

visible invisible

v

becoming visible

at the same

time.

of the revolution as the moment of something

becoming invisible and something

becoming visible at the same

time.

something becoming invisible and something

becoming visible

visible invisible

v

A video of a microphone trembling on an empty stage right after Lukashenko walked away from it, after workers chanted “Leave! Leave!” MZKT, Minsk, August 2020.

The image of an empty factory or work space (at the vehicle part producer’s BELCARD JSC in Hrodna, Belarus).

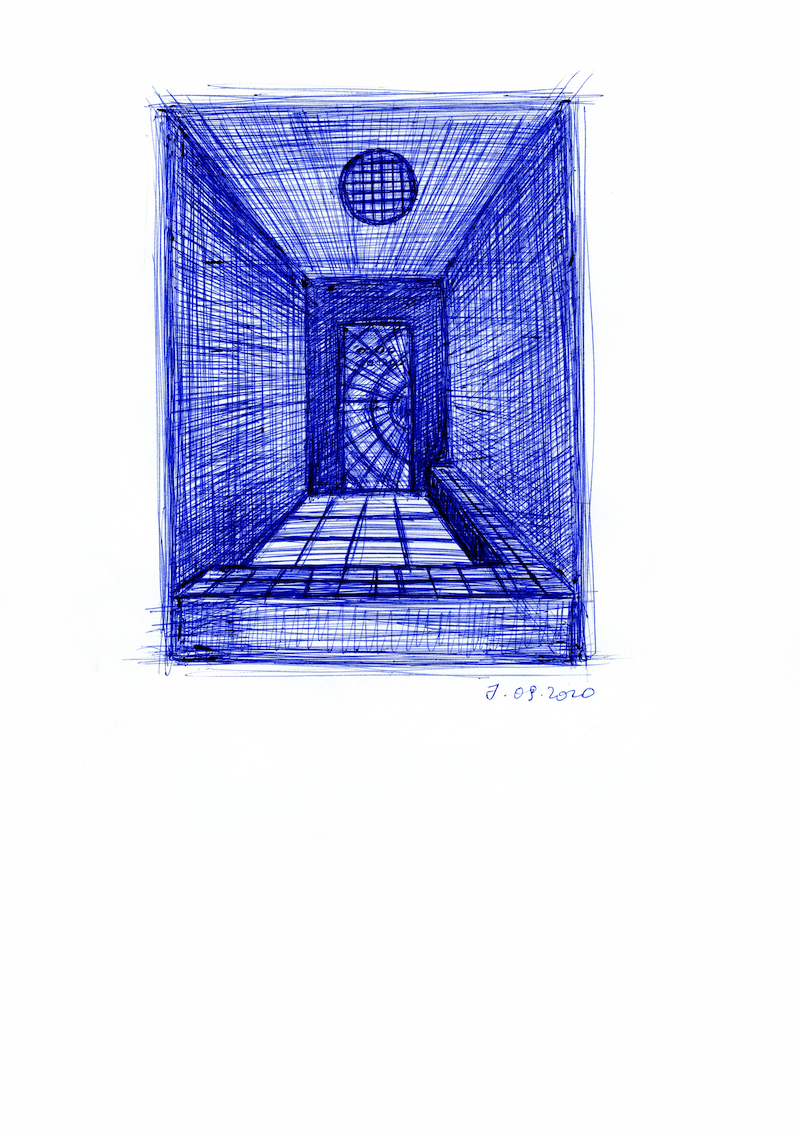

Two series of drawings made by philosopher Olga Sharaga and artist Nadya Sayapina during their imprisonment in Belarus.

During the strike, Belarusian state TV channel “Belarus 1” live-broadcast an empty studio.

The image of an empty factory or work space (at the vehicle part producer’s BELCARD JSC in Hrodna, Belarus).

Two series of drawings made by philosopher Olga Sharaga and artist Nadya Sayapina during their imprisonment in Belarus.

During the strike, Belarusian state TV channel “Belarus 1” live-broadcast an empty studio.

Olia writes: “When I came to the National Library of Belarus this autumn, I noticed a white bracelet on the hand of one of the workers. This meant she was voting against the current government. We were alone in the room and I decided to ask: ‘Did you go on strike?’ She replied that, oh, even if we were on strike, no one would have probably noticed. But they have a flag, and they joined various protests and they joined solidarity actions, some were detained. Since then, I can’t stop thinking about the unnoticed strike of the library workers”.

E: Yeah, I mean, it's interesting, because we first met before the Belarusian revolution. The context of that revolution is a specific one, different from maybe the Arab Spring or the protests in Turkey or the others I looked at before, because in Belarus you still had this sort of post-Soviet, but not exactly post-socialist situation. Something between the GDR of the late 80s and the purely neoliberal context of those other, more recent revolutions.

O: Many of those active during the 2020 protests in Belarus were younger people, in their 20s, or even 30s, who didn't experience the perestroika and earlier anti-government protests in the 90s. Many actually got politicised only during this new revolution. People of the older generations, by contrast, were largely disappointed and tended to share a disbelief in the possibility of the protest. I think this was mostly because they had seen previous protest movements and political organising fail to change the regime.

Several photos documenting an award ceremony for members of the Belarusian special police forces after a wave of anti-government protests. The faces of the police are cropped out to protect their identity. The photos instead focus on the bunches of white roses and their hands.

O: The silent protests [in 2011 in Belarus] might have been a way of testing the limits of repression — if you don't do anything, just gather in the street, are you still persecuted? At the same time, there is a danger of overestimating the power of your body and this gesture of disrupting public space with your presence. Sometimes to annoy the regime or test its limits is not enough.

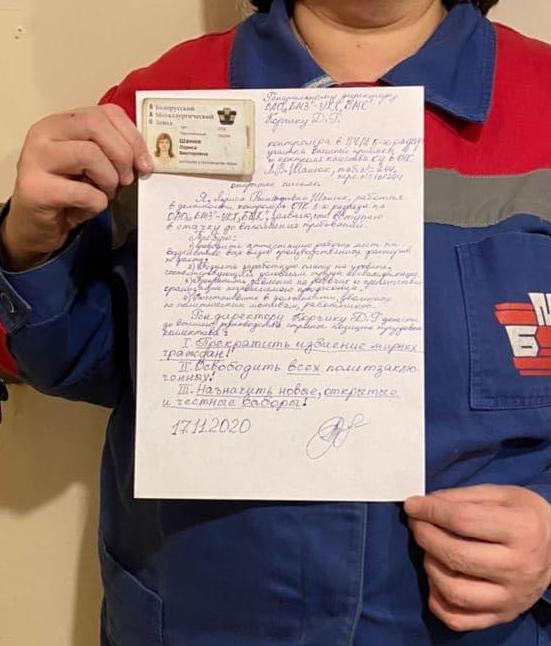

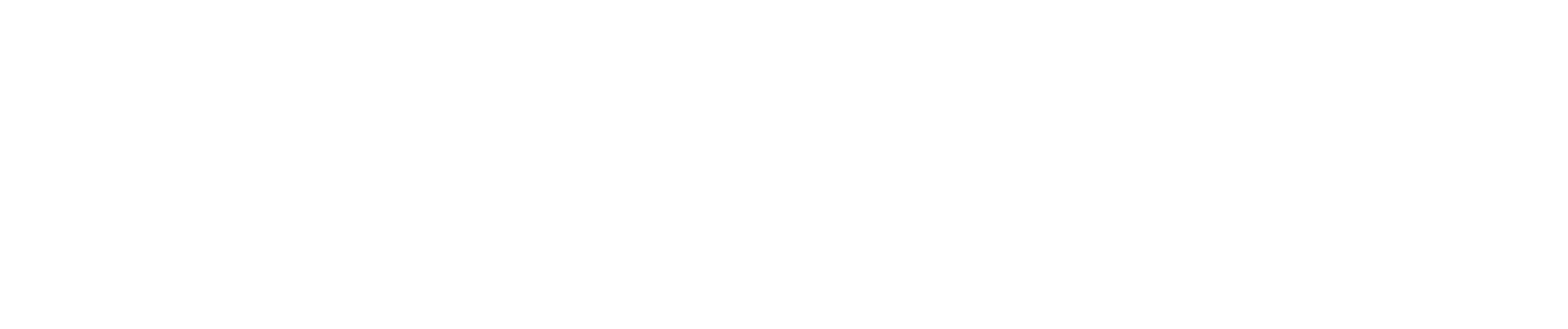

On 15 August 2020, after the post-elections protests’ crackdown, the artists and cultural workers protested against state violence in front of the Palace of Arts in Minsk by holding printouts documenting police violence.

O: I am not sure where the white sheet of paper as a symbol of resistance came from in Belarus and why the colour of white was chosen as a symbol of protest. But during the elections, one way to signal that one voted against the current government, in case of incorrect vote counts, was to wear white bracelets or white clothes. This allowed for independent observers to count this way, and for others to see how many around you are against the government.

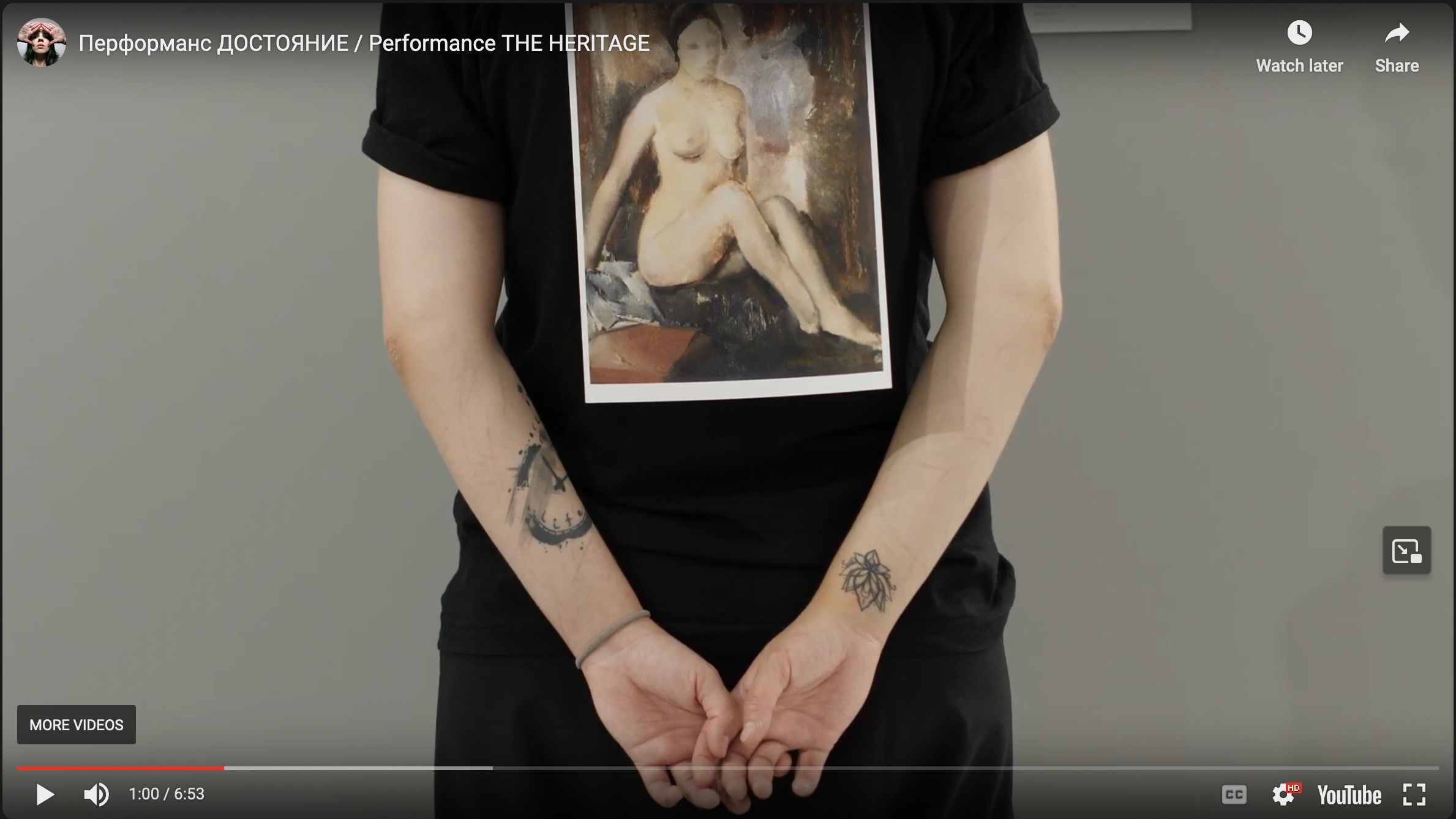

The performance piece Heritage (Dostoyanie) by artist Nadya Sayapina took place in the ArtBelarus gallery on July 1st 2020. Shparaga descibes the event like this: “The artist invited cultural workers to spend several hours in the exhibition space replacing and embodying the missing artworks with a reproduction on their back.”

“For two hours, artists, curators, and other representative of the art scene, [...] most of them women and all dressed in black, stood together and looked at the absent paintings at close range. Each one of them had a photo of one of the confiscated paintings pinned to their back.”

“For two hours, artists, curators, and other representative of the art scene, [...] most of them women and all dressed in black, stood together and looked at the absent paintings at close range. Each one of them had a photo of one of the confiscated paintings pinned to their back.”

In Jena, GDR, in 1977, dissident author and psychologist Roland Jahn carried a white sheet of paper in the annual official first of May demonstration to protest against censorship.

In 2019 blogger and civil rights activist Aslan Sagutdinov held a white sheet of paper at the central Abay Square in Oral, Kazakhstan to test whether he could get detained for holding an empty placard, and he got arrested.

In Belarus in 2020 people put white sheets of paper up in their windows as a sign of support for the revolution.

In Beijing, in November 2022, people held up white sheets of paper in front of their faces in protest against the government’s prohibition of protest.

In Russia in 2022, people were holding up white sheets of paper to protest against the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In 2019 blogger and civil rights activist Aslan Sagutdinov held a white sheet of paper at the central Abay Square in Oral, Kazakhstan to test whether he could get detained for holding an empty placard, and he got arrested.

In Belarus in 2020 people put white sheets of paper up in their windows as a sign of support for the revolution.

In Beijing, in November 2022, people held up white sheets of paper in front of their faces in protest against the government’s prohibition of protest.

In Russia in 2022, people were holding up white sheets of paper to protest against the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

O: When the protests started, I couldn't work for several months because it felt irrelevant to do art at that moment, other forms of engagement felt more necessary. For me it also always takes time to make sense of what is going on. I can't do those rather emotional or formal works, which is often the kind of art made during revolutions, driven by the feeling of urgency.

O: The invasion in Ukraine started when in Belarus it was already very hard to protest, thousands of people had already left fleeing state repressions, there were already thousands of prisoners and total state and police control, and people were also already very traumatised and exhausted. And many people, I think, are now actually disillusioned with peaceful protest.

Writing about revolution in Egypt from 2011, Asef Bayat talks of the “underlying but invisible dissent brewing in societies that otherwise appear sound and secure”. “What if people express dissent, but it goes unnoticed or overlooked by elites, authorities, or observers as simply everyday bickering of little political significance?” Fragmented, but similar activities of large numbers of ordinary people trigger much social change: poor people building homes; installing tap water; phone lines; spreading their merchandise out on the urban sidewalks; the international migrants crossing borders to find new livelihoods; the women striving to go to college; playing sports; working in public; conducting “men’s work”; or choosing their own marriage partners....

This is what he calls the politics of the “non-movements” - a politics that existed before, exploded and invigorated themselves during, and continued after the Egyptian revolution.

This is what he calls the politics of the “non-movements” - a politics that existed before, exploded and invigorated themselves during, and continued after the Egyptian revolution.

In an essay from 2021, Olia Sosnovskaya writes: “Precisely because a march has an end point, resistance continues alongside public manifestations, within self-organized infrastructures and employing mundane and intimate gestures. It trespasses into daily practices and bodies, with their fragility and irregular rhythms”. In Belarus, in 2020, as repressions increased, the protests got increasingly subtle. Marching could not be anymore distinguished from a walk, or queueing, or the very presence of your body in the public space; also perpetuated by the paranoia of the regime. Where protest has become invisible, everything can be a protest.

Vaclav Havel writes about the Czech underground and dissident cultures of the 1970s as “parallel structures” or the “parallel polis”: “The complex ferment that takes place within it goes on in semi-darkness, and by the time it finally surfaces into the light of day as an assortment of shocking surprises to the system, it is usually too late to cover them up in the usual fashion. Thus they create a situation in which the regime is confounded, invariably causing panic and driving it to react in inappropriate ways.”

O: I think the mainstream perception of revolutionary change is some kind of disruption or interruption. But I think, because of the experience of revolution in Belarus which was also the experience of exhaustion and failure and fatigue, the change is more complicated than disruption or singular event. It happens in a process and is often invisible.

E: If nothing is a protest.. if literally doing nothing is considered a protest, then everything becomes a protest and the state implodes, it becomes pure paranoia. It was a bit like that in the late GDR.

Bayat writes: “On the other hand, the labor-versus-capital lens of reductionist Marxism tends to downplay or otherwise reduce the multilayered sources of subaltern dissent (gender, age, status, or social standing)”

Johanna Hedva writes: “So, as I lay there, unable to march, hold up a sign, shout a slogan that would be heard, or be visible in any traditional capacity as a political being, the central question of Sick Woman Theory formed: How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?”

In 2017 polish philosopher and activist Ewa Majewska writes: “Social movements, protests and mobilizations, as well as theorists, reclaim the necessity of overcoming the heroic, patriarchal and exceptional modes of agency. The notion of weak resistance provides such opportunity, allowing us to explain the political agency of the counterpublics of the common. It also helps to imagine the antifascist future.”

Johanna Hedva writes: “I thought of all the other invisible bodies, with their fists up, tucked away and out of sight”.

In an essay from 2021, Elske writes:

“The word “visible” remains visible within the word “invisible”. Cover up the “in”, and it appears. The prefix negates as much as it preserves.”

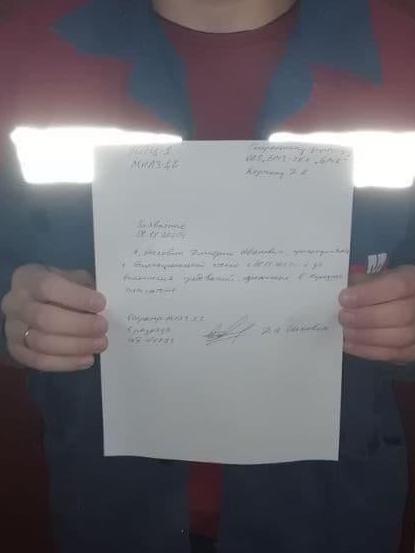

In her project “Invisible Trauma” Lesia Pcholka took photos of a white sheet of paper taped to to the inside of a window which blocks the surrounding landscape.

O: For me, it's mainly a question of representation. Against the spectacularity of revolution, the idea that it's always about a huge mass of people carrying flags. But what about this energy which we draw on, the new relationships being established or when you are just not allowed to document anything because of security concerns? Certain things are kept invisible, and it is important not to disregard something that cannot be represented.

E: That reminds me of a situation at the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when there was an online conference and one participant who was attending on Zoom from Kyiv. He was sitting in his flat in front of his window and one could see that he had put several strips of white tape across the window behind him to prevent it from shattering in the event of an air-strike.

In the late 80s, East German artist Kurt Buchwald made a series of photos in public places. In each his body blocks out most of the urban landscape behind him.

In October 2023, the authorities in Minsk banned as subversive an exhibition of naive paintings of the forest. The artist had called the forest a place of refuge.

E: Of course, many of the so-called underground artists, whose work was invisible as art, because it did not fit the official categories of what art is, and especially the work of woman artists, become invisible again in the categories and the economies of the Western dominated Germany after unification.

Havel talks of becoming a dissident as the crossing of an invisible line. You know that you crossed it only through the reaction of the oppressor.

“From personal experience, I know that there is an invisible line you cross – without even wanting to or becoming aware of it – beyond which they cease to treat you as a writer who happens to be a concerned citizen and begin talking of you as a ‘dissident’ who almost incidentally (in his or her spare time, perhaps?) happens to write plays as well.”

In his 1978 book “The Power of the Powerless”, Havel called such forms of political life “parallel structures.” Within the cultural field, these practices were referred to as “second culture”.

“From personal experience, I know that there is an invisible line you cross – without even wanting to or becoming aware of it – beyond which they cease to treat you as a writer who happens to be a concerned citizen and begin talking of you as a ‘dissident’ who almost incidentally (in his or her spare time, perhaps?) happens to write plays as well.”

In his 1978 book “The Power of the Powerless”, Havel called such forms of political life “parallel structures.” Within the cultural field, these practices were referred to as “second culture”.

In the text “The invisible third man” Christian Schneider talks of the dissident as someone who lives in the real world, and a utopian world at the same time. He also calls the dissident as a figure that does not exist in one or both of the two systems - but only between them, in the gaze of the other.

In the dissident cultures of the Eastern bloc, political messages were often hiding between the lines. In the GDR and in the Soviet Union, between the lines could mean: hiding contemporary critique in existing myths and stories. To convey a message between the lines, to hide it, could also be achieved by simply repeating, reiterating, seemingly affirming, official rituals, phrases or gestures.

Visible to everyone, without being visible at all. Hidden in plain sight.

Visible to everyone, without being visible at all. Hidden in plain sight.

The fog of war.

Like the Soviet joke about the blank

sheet of paper ("why write anything -

it's all clear to everyone anyway")?

E: I mean, holding a white thing, of course, in a situation of violence is also surrender, which I don't know if that is a gesture that one wants to make in a situation of war. So it's interesting to to see what this war actually does to some of the gestures that I've been working with for so long. That's a good question.

In many eastern European countries, for example in Czechoslovakia after the suppression of the Prague Spring, the literal imperceptibility of actions in public space was both a political strategy and an artistic concept.

In 1968 the Czechoslovakian artist Július Koller retraced the white lines of a tennis court with white chalk in one of his artistic actions.

In Prague artist Milan Knizak did a series of actions in the city center. To passers by, his actions looked completely normal. But some who had been invited by Knizak to come there at a certain time, saw an art performance.

In the GDR, art by non-conforming artist was either not shown or simply not recognised as art by official institutions. This was especially true of the work of women artists who were either considered as “lesser painters” or whose works’s status as “art” was called into question.

In 1968 the Czechoslovakian artist Július Koller retraced the white lines of a tennis court with white chalk in one of his artistic actions.

In Prague artist Milan Knizak did a series of actions in the city center. To passers by, his actions looked completely normal. But some who had been invited by Knizak to come there at a certain time, saw an art performance.

In the GDR, art by non-conforming artist was either not shown or simply not recognised as art by official institutions. This was especially true of the work of women artists who were either considered as “lesser painters” or whose works’s status as “art” was called into question.

“Within China, the government doesn’t so much convey its version of events as squelch any discussion of the topic whatsoever. It’s unmentionable. ‘Inside the country, such denialism is not allowed,’ [the Chinese journalist] said. ‘Who knows whether by denying it, you are playing with irony?’ Chinese intellectuals are extraordinarily good at parroting official lines in ways that are satirical and witty.”

A strip of white sand, covering a protest graffiti mourning the protesters killed by police in Minsk, becomes the canvas, or rather becomes part of a new protest image.

Several images of protestors hiding their bodies behind white-red-white protest flags and posters. Belarus, 2020.

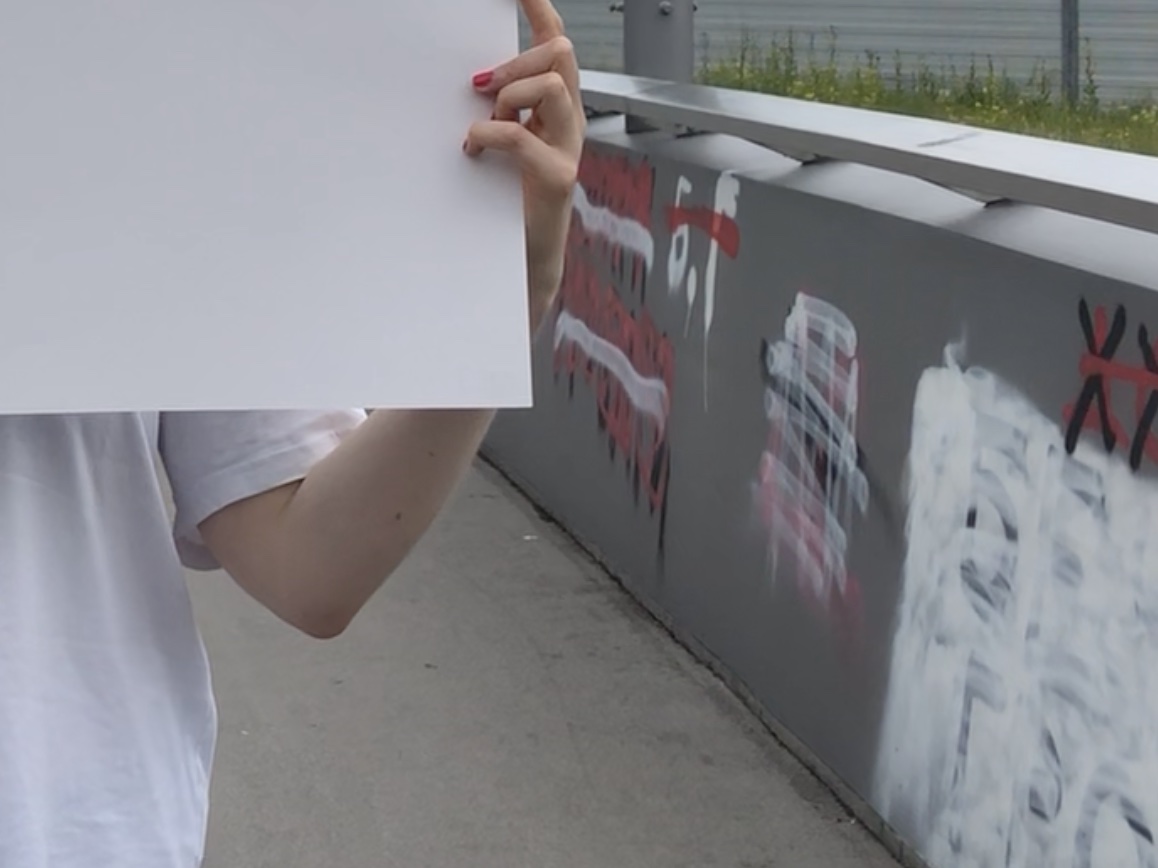

A photo of a solidarity action with detained anarchists by residents of Tractorny district in Minsk. The protestors are holding up / hiding behind: red and white flags, images of arrested comrades, pieces of paper with four handwritten statements.

A close-up of two women in Minsk metro with their faces hidden behind the books: Viktar Martinowich “Revolution” and “Belarusian folk fairy tales”.

A graffiti inside the mine in Salihorsk, Belarus depicting artist Vladimir Tsesler’s poster “Reload” and the inscriptions: people’s ultimatum [for Lukashenka to resign or face a nationwide strike]; Grodno Azot [state-run chemical enterprise on strike].

Several images of protestors hiding their bodies behind white-red-white protest flags and posters. Belarus, 2020.

A photo of a solidarity action with detained anarchists by residents of Tractorny district in Minsk. The protestors are holding up / hiding behind: red and white flags, images of arrested comrades, pieces of paper with four handwritten statements.

A close-up of two women in Minsk metro with their faces hidden behind the books: Viktar Martinowich “Revolution” and “Belarusian folk fairy tales”.

A graffiti inside the mine in Salihorsk, Belarus depicting artist Vladimir Tsesler’s poster “Reload” and the inscriptions: people’s ultimatum [for Lukashenka to resign or face a nationwide strike]; Grodno Azot [state-run chemical enterprise on strike].

“I/we Igor Olinevich, Nikolai Dedok, Dmitry Dubovsky, Sergei Romanov, Dmitry Rezanovich together!”

“Anarchists!!! You - are not terrorists! You - are our heroes! You - fought for the future of Belarus! You - are brave! And now we will fight for you!!!”

“Citizens!! Future is in our hands! Fascism shall not pass!! We - are stronger and we - will win!! Live Belarus!”

“To fight is to remember.”

E: I would say it's over, but I would say it's not completed. I think the revolutionary energy did continue for much longer than is generally acknowledged. After the unification, the revolution wasn't even invisible, because there were still protests, but they have been invisiblized as part of the revolution. For me it's not over in the sense that I still draw on this energy. I still draw on the incompleteness of that revolution.

In September 2020 some of the striking Belaruskali miners decided to stay underground and refuse to return to the surface after a night shift.

O: For me revolution is also about the experience in the bodies and the relationships, it is something that can’t be just unlearned. It didn't change the political system. But I think it did much more. While in a situation of a rapid change of the political regime, there is often a danger that there is no actual change, because politics is not just about who is the president, but how people live together and engage.

Olga Shparaga writes: “Under the surface the protests continued in the mode of peaceful partisan tactics.”

Johanna Hedva writes: “I listened to the sounds of the marches as they drifted up to my window. Attached to the bed, I raised up my sick woman fist, in solidarity”.

O: The war really changed everything. Is it still possible to claim the continuity of revolution? Are subtleness and slowness justified in the face of the urgency and brutality of the war?

The short videos and images of this collage were made by Elske Rosenfeld and Olia Sosnovskaya in Vienna in June 2023, during a residency at Bears im Park. Editing and collaging took place in October 2023 at VBKÖ (Austrian Association of Women Artists) Vienna. We thank Georgia Holz and everyone at VBKÖ and Philippe Riéra for making this possible.

For a list of references and all documentary images and videos click HERE.

For a list of references and all documentary images and videos click HERE.